Have you ever thought of a function in Python as more than just a block of code? What if you could store functions in a list, just like you store numbers or strings? If this sounds confusing, don’t worry! You’re about to learn a fundamental Python concept that reveals the true power and elegance of the language.

In this guide, we will explore a key property that proves functions are objects in Python. By the end, you’ll understand how to store multiple functions inside a data structure and call them dynamically, a skill that will significantly level up your coding efficiency.

What Does “Functions are Objects” Mean?

In Python, everything is an object. Integers, strings, lists, and dictionaries are all objects. But what truly surprises many beginners is that functions are objects too. This means that a function, just like the number 5 or the string "hello", can be:

- Assigned to a variable.

- Stored in a data structure (like a list or dictionary).

- Passed as an argument to another function.

This property is a cornerstone of Python’s flexibility. Today, we’ll focus on the second point: storing functions in a list.

Storing Functions in a List: A Practical Example

Let’s make this concept crystal clear with a hands-on example. We’ll create several simple mathematical functions and then store them all in a single list.

First, we define our functions. Notice that these are just regular, everyday functions.

# Define a function for addition

def sum(a, b):

return a + b

# Define a function for multiplication

def multiplication(a, b):

return a * b

# Define a function for exponentiation

def exponent(a, b):

return a ** b # 'a' to the power of 'b'

# Define a function for subtraction

def subtraction(a, b):

return a - bNow, here comes the magic. We create a list called operations and place all these function names inside it. Notice we are not using parentheses (). We are referring to the function objects themselves, not calling them.

# Store all the function objects in a list

operations = [sum, subtraction, exponent, multiplication]At this point, our list operations doesn’t contain numbers or strings. It contains four function objects, sitting in a row, ready to be used.

How to Dynamically Call Functions from a List

Now that we have our functions in a list, how do we use them? The answer is a simple for loop.

Let’s define our two input variables:

x = 5

y = 10Next, we’ll loop through our operations list and call each function one by one.

# Loop through each function in the operations list

for func in operations:

# Call the current function with x and y, then print the result

result = func(x, y)

print(f"The result of {func.__name__} is: {result}")Let’s break down what happens inside the loop:

- First Iteration:

funcis assigned thesumfunction. The lineresult = func(x, y)becomesresult = sum(5, 10), which returns15. - Second Iteration:

funcis assigned thesubtractionfunction. The line becomesresult = subtraction(5, 10), which returns-5. - Third Iteration:

funcis assigned theexponentfunction. The line becomesresult = exponent(5, 10), which returns9765625(5 raised to the 10th power). - Fourth Iteration:

funcis assigned themultiplicationfunction. The line becomesresult = multiplication(5, 10), which returns50.

When you run the complete code, the output will be:

The result of sum is: 15 The result of subtraction is: -5 The result of exponent is: 9765625 The result of multiplication is: 50

This demonstrates the power and simplicity of treating functions as objects. You can easily manage, iterate over, and execute a collection of functions without repetitive code.

Why Is This Concept So Powerful?

You might be thinking, “I could have just called each function individually.” While true for four functions, imagine you have dozens or even hundreds of operations to perform. Using a list of functions makes your code:

- Cleaner: Avoids repetitive lines of code.

- More Maintainable: To add a new operation, you just define the function and add it to the list.

- Dynamic: You can build the list of functions based on user input or other conditions during runtime.

This pattern is extremely useful in building command-dispatcher systems, menu-driven applications, and plugin architectures.

Ready to Go from Basics to Pro?

You’ve just taken a big step into understanding Python’s advanced, yet intuitive, nature. Mastering concepts like this is what separates beginners from proficient developers. If you enjoyed this glimpse into Python’s power, imagine what you could achieve with a structured learning path.

A comprehensive course can guide you through all the essential concepts, from fundamentals to advanced topics like decorators and object-oriented programming, with expert guidance and real-world projects to solidify your skills.

If you’re serious about mastering Python, check out our pre-recorded python comprehensive video course.

Conclusion

In this post, you learned that in Python, functions are first-class objects. This allows you to store them in data structures like lists and call them dynamically. We walked through a practical example where we stored four mathematical functions in a list and used a for loop to execute them all with a single, clean block of code. This is a powerful paradigm that opens the door to writing more efficient and flexible programs. Keep practicing with this concept—try storing functions in a dictionary next to create a simple calculator!

Common Questions About Functions as Objects

Can I store functions from built-in modules in a list?

Yes, absolutely! For example, you can do my_list = [len, str.upper, print]. Just remember to reference them without parentheses.

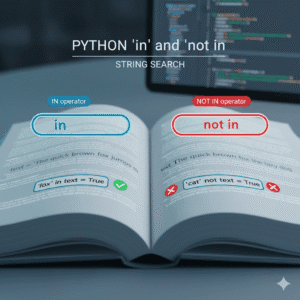

What’s the difference between a function name with and without parentheses?

Using the function name without parentheses (e.g., sum) refers to the function object itself. Using it with parentheses (e.g., sum(5, 10)) calls or executes the function.

Are there other data structures I can use besides lists?

Yes, dictionaries are very commonly used for this purpose. For instance, you could create a calculator dictionary: calc = {'add': sum, 'multiply': multiplication} and then call functions with calc['add'](5, 10).