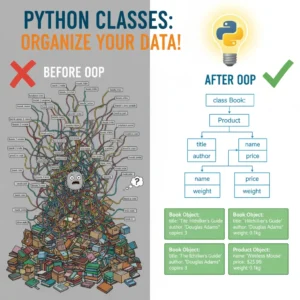

Have you ever created a Python class with some data, like a Book with a title and author, but then felt stuck? You might be printing that data from outside the class, which works, but it’s not the “Pythonic” way. It’s like having a car where you have to open the hood to start the engine manually instead of just turning a key.

In object-oriented programming (OOP), objects shouldn’t just hold data; they should also have behavior. In this post, you’ll learn how to give your Python classes behavior by creating methods, and you’ll finally understand the mysterious self keyword that every beginner encounters. By the end, you’ll be structuring your code like a pro, making it more organized, reusable, and powerful.

What Are Class Methods (Instance Methods)?

In our previous analogy, a Book class can have properties like title, author, and pages. These are the object’s data, or its “state.” But what can the object do? In the context of an e-commerce website, a book should be able to display its own information.

This “display” action is a behavior. In Python, we define behaviors for our classes using methods. Think of methods as functions that live inside a class and are designed to work on the specific object (instance) of that class.

Let’s look at a basic class without methods:

class Book:

def __init__(self, title, author, pages):

self.title = title

self.author = author

self.pages = pages

# Creating objects (instances) of the Book class

book1 = Book("Five Point Someone", "Chetan Bhagat", 250)

book2 = Book("The Alchemist", "Paulo Coelho", 208)

# Printing the data from outside the class

print(f"Title: {book1.title}, Author: {book1.author}, Pages: {book1.pages}")

print(f"Title: {book2.title}, Author: {book2.author}, Pages: {book2.pages}")This works, but the printing logic is separate from the Book class. What if we want to change how a book is displayed in ten different places in our code? We’d have to make ten changes. The better way is to let the Book class handle its own display.

Creating Your First Class Method

Let’s add a display method to the Book class. This encapsulates the behavior within the class.

class Book:

def __init__(self, title, author, pages):

self.title = title

self.author = author

self.pages = pages

# This is an instance method

def display(self):

"""Displays the book's details."""

print(f"Title: {self.title}, Author: {self.author}, Pages: {self.pages}")

# Creating objects

book1 = Book("Five Point Someone", "Chetan Bhagat", 250)

book2 = Book("The Alchemist", "Paulo Coelho", 208)

# Calling the method on the objects

book1.display()

book2.display()Output:

Title: Five Point Someone, Author: Chetan Bhagat, Pages: 250 Title: The Alchemist, Author: Paulo Coelho, Pages: 208

Notice how much cleaner this is? Now, every Book object knows how to display itself. If we need to change the display format, we only change it in one place: inside the display method.

Demystifying the self Keyword

This is the most crucial concept to grasp. You probably noticed the self parameter in the __init__ method and our new display method. What is it, and why is it there?

When you call a method on an object, like book1.display(), Python automatically passes the object itself as the first argument to the method. By convention, we name this first parameter self.

- When you write

book1.display(), Python secretly doesBook.display(book1). - Inside the method,

selfbecomes a reference tobook1. - So,

self.titleinside the method is the same asbook1.titleoutside of it.

This is why self is essential: it gives the method access to the specific object’s data. When book2.display() is called, self refers to book2, so self.title correctly gets book2‘s title.

What Happens Without self?

Let’s see what happens if we forget self in our method definition.

class Book:

def __init__(self, title, author, pages):

self.title = title

self.author = author

self.pages = pages

# INCORRECT: Forgot the 'self' parameter

def display():

print(f"Title: {title}, Author: {author}, Pages: {pages}")

book1 = Book("Five Point Someone", "Chetan Bhagat", 250)

book1.display()Running this code will give you a TypeError:TypeError: display() takes 0 positional arguments but 1 was given

Even though it looks like you called display() with no arguments, Python did pass one—the book1 object. The method wasn’t set up to receive it, causing the error. Always remember to include self as the first parameter in your instance methods.

Putting It All Together: A Cohesive Example

Let’s build a more practical example to solidify these concepts. We’ll create a method that provides a formatted summary for a web page.

class Book:

def __init__(self, title, author, pages, price):

self.title = title

self.author = author

self.pages = pages

self.price = price

def display_info(self):

"""Displays basic info in the console."""

print(f"'{self.title}' by {self.author} - {self.pages} pages.")

def get_html_snippet(self):

"""Returns an HTML-formatted string for a webpage."""

return f"""

<div class='book-card'>

<h3>{self.title}</h3>

<p><strong>Author:</strong> {self.author}</p>

<p><strong>Length:</strong> {self.pages} pages</p>

<p><strong>Price:</strong> ${self.price}</p>

</div>

"""

# Create a book instance

my_book = Book("The Immortals of Meluha", "Amish Tripathi", 390, 15.99)

# Use its behaviors

my_book.display_info()

# This output could be inserted directly into an HTML file

html_output = my_book.get_html_snippet()

print(html_output)This example shows the power of methods. The Book class is now responsible for both its data and how that data is presented in different contexts (console vs. web).

Ready to Go from Basics to Pro?

Understanding class methods and self is a huge leap forward in your Python journey. You’re no longer just storing data; you’re building intelligent, self-contained objects that can power complex applications. To truly master Python and move from following tutorials to building your own real-world projects, structured learning is key.

If you’re serious about mastering Python, check out our pre-recorded python comprehensive video course.

Conclusion

In this guide, you’ve unlocked a fundamental concept in Python OOP: class methods. You learned that methods define the behavior of objects, and the self keyword is the magic link that connects a method to the specific object calling it. This allows each object to maintain its own state and actions, leading to cleaner, more modular, and more maintainable code. Keep practicing by adding different methods to your classes—perhaps a apply_discount method for a Product class or a full_name method for a User class. The world of OOP is now at your fingertips!

Common Questions About Python Class Methods

Q: Can I use a name other than self?

A: Technically, yes. self is not a reserved keyword but a very strong convention. Every Python programmer expects to see self, so using anything else (like this or me) will confuse others and is highly discouraged.

Q: What’s the difference between a function and a method?

A: A function is a standalone block of code defined with def. A method is a function that is defined inside a class and is intended to be called on an instance of that class. The key difference is that a method automatically receives the instance (self) as its first argument.

Q: Do the __init__ constructor and other methods always need to be in a class?

A: No, you can have a class with no methods (only data), or without an __init__ method (though it’s very common). However, to create useful, behaving objects, you will almost always use the __init__ method to set up initial state and other methods to define behaviors.