Have you ever stored a number in a variable? Or appended a string to a list? If so, you’re already familiar with working with objects in Python. But what if I told you that the functions you define are also objects? This powerful concept is a cornerstone of advanced Python programming, enabling elegant and flexible code designs.

In this guide, we will demystify what it means for functions to be objects. You’ll learn one of the key proofs of this concept: how to return a function from another function. By the end, you’ll have a new, deeper understanding of Python that will open doors to more sophisticated programming techniques.

What Are “First-Class Objects” in Python?

In Python, everything is an object. Integers, strings, lists, and dictionaries are all objects. But “first-class object” means something more specific. It means that a function can be treated just like any other variable.

This grants functions several special abilities:

- They can be assigned to a variable.

- They can be stored in data structures like lists or dictionaries.

- They can be passed as an argument to another function.

- They can be returned as a value from another function.

Today, we’re focusing on that last, powerful property.

Demonstrating Functions as Objects: Returning a Function

The best way to understand a concept is to see it in action. Let’s write some code that proves a function can be created and returned from inside another function.

Step 1: Setting Up Our Functions

Let’s start with two simple functions in the global scope.

def greet():

print("Hello")

def world():

print("World")

# We can call them directly

greet() # Output: Hello

world() # Output: WorldIn this setup, both greet and world are known to the entire program. But what if we want to hide the world function and make it accessible only through greet? This is where inner functions come in.

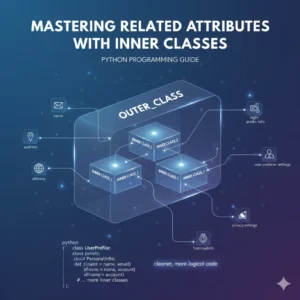

Step 2: Creating an Inner Function

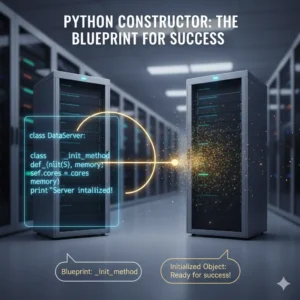

We can define a function inside another function. This inner function is local to the outer function, much like a local variable.

def greet():

print("Hello") # This prints first

# Defining an inner function

def world():

print("World")

# Returning the inner function

return world

# Let's see what happens when we call greet()

result = greet()

print(result)When you run this code, you’ll see two things:

Hellois printed because thegreet()function was executed.- You’ll see an output similar to

<function greet.<locals>.world at 0x000001C6B42A8E50>.

This mysterious output is the key! The print() function doesn’t know how to display a function “object,” so it shows its memory address instead. This is the same behavior you’d see with any other object and is our first proof that a function is an object.

Step 3: Understanding the Scope

Before we call the inner function, let’s prove it’s truly local. If we try to call world() from the main program, it will fail.

def greet():

print("Hello")

def world():

print("World")

return world

# This will cause a NameError!

world()Running this code gives you: NameError: name 'world' is not defined. This confirms that the world function exists only within the namespace of the greet function. It’s a local object, invisible to the outside world unless we explicitly return it.

Step 4: Calling the Returned Function

Now for the magic. We captured the returned world function in the variable result. Since result now holds the function object, we can call it by adding parentheses ().

def greet():

print("Hello")

def world():

print("World")

return world

# greet() returns the 'world' function, which we store in 'y'

y = greet() # Output: Hello

# Now 'y' holds the 'world' function. We can call it!

y() # Output: WorldAnd there you have it! We successfully called the inner world function from outside its original scope. The greet() function acted as a factory, creating and returning a new function object for us to use.

Why Is This Useful? A Glimpse into Practical Applications

You might be wondering, “This is cool, but when would I actually use it?” This pattern is the foundation for several advanced techniques:

- Closures: The inner function can “remember” the state of the outer function’s variables even after the outer function has finished executing.

- Decorators: This is perhaps the most common use case. Decorators are functions that modify the behavior of another function, and they rely heavily on the concept of returning functions.

- Function Factories: You can create functions that generate other, more specialized functions based on input parameters.

Ready to Go from Basics to Pro?

Understanding that functions are objects is a major milestone in your Python journey. It separates novice coders from those who can write elegant, efficient, and professional-grade code. If you’ve enjoyed unraveling this concept, imagine what you could achieve with a structured learning path.

Mastering these fundamentals is crucial for tackling real-world projects, web development with frameworks like Django, and data science libraries. If you’re serious about mastering Python, check out our pre-recorded python comprehensive video course.

Conclusion

In this guide, we explored one of the core tenets of Python: functions are first-class objects. We demonstrated this by defining a function inside another function and returning it as an object. This ability allows for powerful programming paradigms like decorators and function factories, making your code more modular and expressive.

Keep practicing with these concepts. Try creating your own outer function that returns different inner functions based on an argument. The more you experiment, the more intuitive these powerful ideas will become.

Common Questions About Functions as Objects

Can I return a function that has arguments?

Absolutely! The inner function can have its own parameters. When you call the returned function object, you simply pass the arguments as you normally would.

def multiplier_factory(factor):

def multiplier(x):

return x * factor

return multiplier

double = multiplier_factory(2)

print(double(5)) # Output: 10What’s the difference between returning a function and calling a function?

Returning a function (return world) gives you the function object itself to be used later. Calling a function (world()) executes its code immediately and returns the result (e.g., None for a simple print function).

Is this the same in all versions of Python?

Yes, the concept of functions as first-class objects has been a fundamental part of Python since its early days.